Astronomical POV on Galaxy10 Anomaly Detection

“Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.”

— Carl Sagan

In the past week, I revisited my previous projects to brainstorm ideas for upgrading them. The first project that came to mind was Galaxy Morphology Classification using ConvNeXtTiny. I challenged myself by limiting the resources available to the free-tier Kaggle Notebook to avoid spending too much time or resources. Additionally, I wanted to make the most out of the dataset, so I decided to use the same Galaxy10 DECals dataset.

Some Background on the Dataset

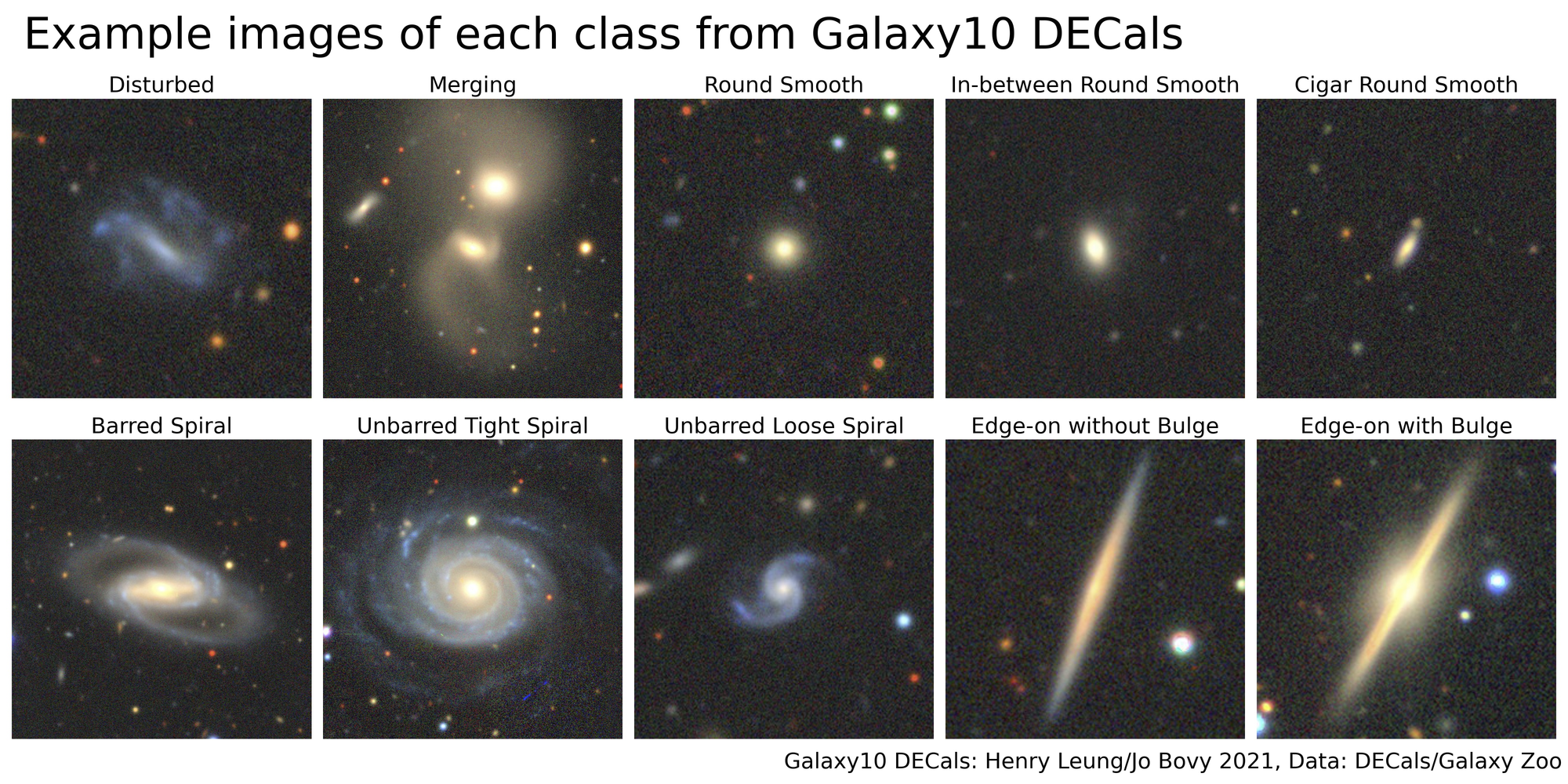

The Galaxy10 DECals dataset was designed as an astronomical counterpart to the CIFAR-10 dataset. It contains images of galaxies collected from a long history of sky surveys, including the Galaxy Zoo project, if you’ve heard of it. The labeling process was carried out by volunteers using decision trees created by professionals. However, some classifications may be inaccurate, or certain galaxies may be difficult to distinguish visually. The numbers 0 to 9 in the dataset are coded as follows:

Galaxy10 dataset (17736 images)

├── Class 0 (1081 images): Disturbed Galaxies

├── Class 1 (1853 images): Merging Galaxies

├── Class 2 (2645 images): Round Smooth Galaxies

├── Class 3 (2027 images): In-between Round Smooth Galaxies

├── Class 4 (334 images) : Cigar Shaped Smooth Galaxies

├── Class 5 (2043 images): Barred Spiral Galaxies

├── Class 6 (1829 images): Unbarred Tight Spiral Galaxies

├── Class 7 (2628 images): Unbarred Loose Spiral Galaxies

├── Class 8 (1423 images): Edge-on Galaxies without Bulge

└── Class 9 (1873 images): Edge-on Galaxies with Bulge

Here are some examples of images from each class. The images are credited to the original author of the dataset.

As seen from the images above, it’s clear that distinguishing between them is really challenging, especially when it comes to the spiral galaxies and the round, smooth groups. My previous galaxy classification projects showed higher accuracy when considering the top-3 accuracy, but the top-1 accuracy wasn’t as impressive.

Motivation

When brainstorming ideas for the project, I started thinking about how machine learning has revolutionized many fields by automating tasks. The original goal of the galaxy image classification project was to speed up the identification process. With large datasets, there can also be some outlier instances, whether due to distinct traits or significant imaging noise and artifacts.

So, I decided to build on ideas from a previous project where I used autoencoders to detect anomalies in images. This time, I had to scale things down due to limited resources, so I used a pretrained model (ResNet50) and encoded the extracted features instead. I also explored other clustering algorithms to identify anomalies. You can find the detailed implementation and technical details on my GitHub Repo, so feel free to check it out if you’re interested.

Results and Interpretation

As a side note, this blog is meant to focus more on the astronomical and astrophysical aspects (at least from what I know), so I won’t be diving into the technical interpretation or statistical results here. However, I’ve already covered those in the reports section of my repo, so feel free to check it out if you’re interested.

Let’s start with this image, which is the result of running anomaly detection using ensembled models. The images are from the testing dataset, representing a random subset of about 10% of the entire dataset.

I’ve already shared some observations in the earlier report. Specifically, samples with IDs: 1023, 1154, 1373, 1477, 1532, and 1673 possibly represent interacting galactic systems. However, I can’t confirm this hypothesis, as we don’t know if these galaxies are at similar distances. They may just appear close to each other in the night sky while being unrelated, as they belong to entirely different systems. For example, the famous Winnecke 4 (Messier 40) was originally thought to be a binary system but later found to be an optical double—two stars that appear close together by chance but aren’t physically bound.

(Image credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA - M40 (Winnecke 4))

On the other hand, Sirius, the brightest star in Canis Major (The Greater Dog), was discovered to be a binary system despite its companion being less visible. Determining distances for galaxies and stars uses different methods. Most stars are relatively close to us, and we can measure their distances using trigonometric parallax, observing their positional shift over six months.

Galaxies, however, are much farther away, as they lie beyond the Milky Way. The parallax method only works up to about 100 parsecs (roughly 326 light-years or 3 quadrillion kilometers). Beyond this range, most galaxies are millions of parsecs away (megaparsecs). At these distances, we observe an interesting phenomenon: the light from galaxies gets distorted and shifted toward red wavelengths, a phenomenon known as redshift. Galaxies with larger redshifts are moving away faster, as described by Hubble’s law. For galaxies with a small redshift (less than 0.01), we can approximate their distance using:

\[d = \frac{v}{H_0} \approx \frac{zc}{H_0}.\]Here, $H_0$ is the Hubble constant, and $c$ is the speed of light in a vacuum. Using this equation, further analysis can verify whether two apparently close galaxies are physically interacting.

In recent years, interacting galactic systems have captivated researchers due to their role in various cosmic phenomena. For instance, in 2023, researchers modeled a candidate runaway supermassive black hole as a result of interacting galaxies. It’s fascinating to observe a black hole “escaping” its home! With further improvements, this project could potentially serve as a screening tool for large sky surveys, identifying candidates for further exploration. This is especially valuable as galaxies evolve over billions of years like Andromeda, which is predicted to merge with the Milky Way in a few billion years (good luck to those alive then!).

In summary, while some flagged anomalies don’t show any notable traits and could result from statistical errors, others like sample ID 616 exhibit bright spots that resemble imaging artifacts. This suggests the tool could also function as an image-quality screening tool if trained accordingly. This brings us to the end of this blog. I plan to spend my winter break building more astronomy-related projects, and I’ll definitely share them here—stay tuned!